Shostakovich's Piano Sonata No. 2 (cont'd)

Piano Sonata No. 2: Stylistic Analysis

The Sonata consists of three movements (Allegretto, Largo, Moderato) that demonstrate three major aspects of Shostakovich‘s works: dramatic (first movement), lyrical (second movement), and tragic (third movement).

First Movement (Moderato)—Modified Sonata Form

The first movement of the Sonata is in sonata allegro form although as might be expected, the form Shostakovich constructs in this movement strays far away from the traditional (classical) examples of sonata form.

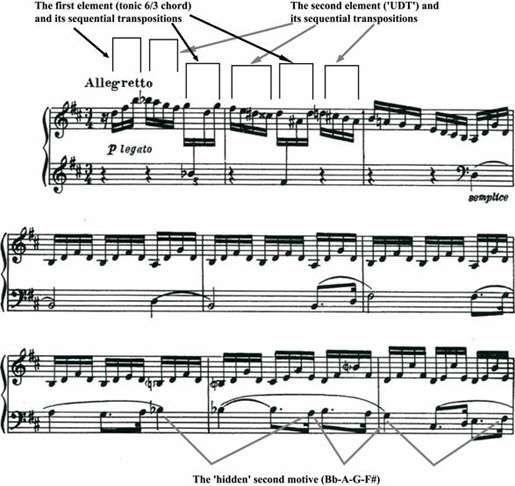

Exposition: In the Sonata, almost every theme forms a section consisting of the local exposition, development, climactic area and conclusion. The primary thematic section of this sonata form is in a 50-bar constant semiquaver motion, combining the exposition and the following development of the theme. It begins from the short introduction exposing the two leitmotives of the Sonata: the first element is an upward B minor six-three (T6/3) chord. The second element exposes the downward tetrachord (four-note structure notated as Bb – A – G – F#) within a diminished fourth. This structure is hereinafter defined as the diminished tetrachord, which will then be explicitly exposed and developed in the theme and variations of the third movement. The diminished tetrachord later becomes Shostakovich’s musical ‘self-portrait’, the most identifiable stylistic element used for the expression of the composer’s ‘self’. (See the musical examples attached to this article.)

There are two distinctive versions of the diminished tetrachords in the Sonata. The first version is the four-note structure notated as Eb – D – C# - B; the second version is the aforementioned structure notated as Bb – A – G – F#. See Example 2. The two tetrachords are hereinafter defined as the Lower Diminished Tetrachord (the ‘LDT’) and the Upper Diminished Tetrachord (the ‘UDT’), respectively. The ‘LDT’ and the ‘UDT’ can be easily distinguished, if transposed, by their structure: the ‘LDT’ consists of half tone - half tone - whole tone; the ‘UDT’ consists of half tone – whole tone – half tone (symmetrical structure). Both diminished tetrachords will later become a modal quintessence of the variation theme in the third movement of the Sonata (see Example 24 on page 24).

Example 2. First Movement, the Primary Theme, first phase.

The two introductory leitmotives appear to be a model for the sequence containing two transpositions (see the first two bars of Example 2). The actual theme starts from the upbeat in bar 3 marked semplice. It introduces the main elements in more detail: bars 4–6 introduce the first element – a deliberate unfolding of the tonic triad. Starting from bar 7, the second element, ‘hidden’ in the melodic contour (starting from Bb), initiates a long unfolding process that can be split into three phases. The first phase ends in bar 17 – an authentic cadence (dominant – tonic progression) in the bass is also ‘hidden’ in a relentless semiquaver motion. The second phase begins at the upbeat to bar 17 – an obvious repetition of the beginning of the first phase, but here it is doubled in sixths and moved from the bottom to the top textural layer. This second introduction of the main motive initiates the intensive development that quickly reaches the climactic point of this section (bars 30–31). Starting from the upbeat to bar 31, the third, climactic phase ‘takes over’ in the development process; here, the first triadic element is transposed to Bb Major. Moreover, the texture becomes denser by the addition of another layer – triads in the middle voice and, starting from bar 35, the main triadic motive, which is doubled in octaves. The primary thematic section ends in bar 51, followed by the four-bar transition.

As can be seen from this discussion, in the primary thematic section Shostakovich employs the polyphonic methods of thematic development (‘phased-in’, ‘non-stop’ development). As will be seen from further analysis, this type of thematic development becomes a pattern for many sections of the Sonata.

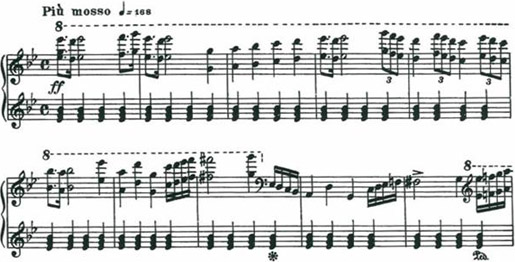

The secondary thematic section of the exposition (Example 3) contrasts with the primary theme in almost all aspects:

Genre: march-like: 3/4 time changes to 4/4 time (in contrast to the song-like first theme); a ‘primitive’ chordal accompaniment (a constantly repeated tonic triad);

Tempo: Significantly faster (Piu mosso): Due to fast tempo, the otherwise typical ‘martial’ episode is perceived rather ironically – very typical of Shostakovich’s grotesque vision (hereinafter referred to as the grotesque or farce effect);

Structure: closed periodic structure (17-bar period);

Texture: ‘pure’ homophonic: the theme in the top layer (doubled in octaves) and the ostinato accompaniment in the bottom layer;

Register: Shostakovich’s favoured ‘marginal’ (extremely high)register – the top note of the theme is G in the fourth octave! (Adds to the grotesque effect);

Key and Mode: B minor changes to Eb Major (distant chromatic mediant tonal relationship). The composer uses almost diatonic (with only one chromatic tone – F#) Lydian major (no Ab in the Eb Major scale).

Dynamics and Articulation: Fortissimo (with diminuendo in the final bar) instead of piano, marcato instead of legato semplice in the primary theme.

Example 3. First Movement, the Secondary Theme.

Grotesque or farce effect: fast tempo, extremely high register, 'trampling' ostinato

Interestingly, the secondary theme of the exposition creates obvious echoes of the prominent march-like theme (known as the ‘invasion’ theme) in the first movement of the Seventh Symphony (completed in 1942, less than a year before the Sonata). See Example 4. Curiously enough, both themes are in the key of Eb Major and are very similar in length (a 17-bar long secondary theme in the Sonata and an 18-bar long ‘invasion’ theme in the Seventh Symphony). In addition, ostinati are applied in the case of both themes: in the Sonata, the left hand part (ostinato of tonic triads), in the Symphony, the tamburo part which accompanies the entire ‘invasion’ episode. Analogously to the Sonata, in the Seventh Symphony the ‘invasion’ (‘evil’) theme creates a major contrast to all other themes of the sonata form. (The difference is that the ‘invasion’ episode of the Seventh Symphony does not seem to possess any irony or grotesque effect, being the truly aggressive image of an imminent enemy.)

Example 4. The Seventh (Leningrad) Symphony, First Movement, The 'Invasion Theme'.

Eb Major, ostinato in tambourine part

The closing theme (Example 5) brings a new, contrasting image. Chromatic and mournful, with its melodic contour looping up and down, it might for example depict someone climbing steps but being repeatedly pushed back. This ‘wailing’ motive is further referred to as a ‘victim’ theme (an absolute opposite to the ‘invasion’ theme). In my view, this episode of the exposition depicts the victim’s persistent attempts to flee. In the first attempt (bars 18–26), the ‘victim’ theme gradually climbs, reaching, after each loop, the E2, F2, F#2, Ab2, Bb2, C3, and finally D3 (in total, the theme, starting from D2, ‘conquers’ the octave!). It is then pushed back to G2 and to C2 (lower than it began). The new loop is shorter (four bars only); most likely, because the victim is exhausted by the first, longer attempt (9 bars). On this occasion it reaches only B2 (bar 30) and is pushed back to Gs and then to Cs. In its final attempt, the ‘victim’ theme reaches Bbs only (bar 34), below the ‘invasion’ theme returns inconspicuously (upbeat to bar 34: in treble clef, A natural reappears), making the ‘victim’ theme simply an insert within the entire secondary thematic section.

Example 5. First Movement, the Closing Theme.

Arrows show the 'conquered' distance (the octave)

between the starting and the top note of the theme.

The ‘victim’ theme, in my perception, pictures victims attempting to escape from prison or from a concentration camp. (Much like the ‘invasion’ episode of the Seventh Symphony, this image can be interpreted dualistically – Nazi regime victims escaping from concentration camps or Communist regime victims escaping from Stalin’s prisons and camps.) The ‘victim’ theme is built on the foundations of the same continuous ‘martial’ accompaniment (part of the ‘invasion’ symbolism), making it thematically symbiotic (a combination of secondary and closing theme elements) and contrapuntal in terms of the methods of thematic development employed. The result of this very ‘Beethovenian’ episode is obviously tragic: the ‘victim’ (‘self’) is eventually forced back, with no hope left of escaping its ‘fate’.

To summarise the above discussion, it should be noted that the formal functions of the exposition are quite ambiguous: the primary theme includes development functions and the secondary and closing themes are merged, both vertically and horizontally, into one section. As a result, the whole exposition actually consists of the two highly contrasting episodes (sections) where the first and the second themes of the sonata form are placed in reverse order: the first theme is more lyrical (expresses the composer’s ‘self’), and the second theme is ‘quasi’ aggressive and plays the role of ‘fate’. Consequently, in this sonata form there are obvious analogies to the most dramatic of Beethoven’s sonatas, which depict a battlefield where the ‘hero’ fights his ‘fate’ (Beethoven’s The Tempest and Appassionata are the best examples). The difference is, again, in the form in which the composer expresses his ‘self’ – unlike Beethoven’s, Shostakovich’s heroes are more lyrical, vulnerable, and fragile, as was Shostakovich’s own personality,17 and the composer typically identifies himself with the heroes of his music.18

Development: The development section itself is relatively short and consists of two sub-sections. The first sub-section (starting in bar 97) is mainly built on the primary and closing thematic elements; the first four bars clearly expose the two leitmotives: the tonic triad followed by the ‘self’ motive – the upward ‘UDT’ (B – C – D – Eb). See Example 6. This section introduces the new key, E minor (the subdominant in relation to the home key – quite typical in classical sonata forms). Interestingly, Shostakovich uses melodic modulation from Eb Major to E minor (as a bridge from the exposition to the development), thus exhibiting ‘common third’ tonal relationships – a sign of post-romantic musical language. Again, it is important to note that the composer applies a Phrygian minor (no F# in the E minor scale).19

Example 6. First Movement. Development—First Section.

Bracketed are the occurrences of the upward 'UDT'.

The second sub-section of the development (bar 138) is functionally ambiguous: the relentless semiquaver gesture returns (for the second time in this movement), lasting another 50 bars and ‘consuming’ the first section of the recapitulation. In my view, bar 138 is a ‘false’ recapitulation, with the tonal (real) recapitulation coming only in bar 168 (the return of B minor).

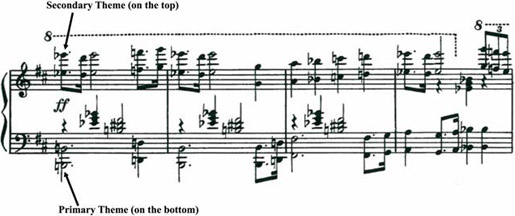

Recapitulation: When comparing this section to the ‘phased-in’ structure of the primary thematic section of the exposition, the most logical explanation seems to be the following: the first phase of the 50-bar episode (bars 138–167) belongs to the development section, while the second phase (the strong climactic area, bars 168–187) belongs to the recapitulation section. Thus, the recapitulation section is the most ambiguous in the first movement – the development and the recapitulation of the primary theme are horizontally merged! This type of recapitulation is here referred to as the absorbed recapitulation (identified only by the home key and Tempo I marking). With no cadences and with continuously increasing dynamics, this section flows directly into the next section, the most original in the entire movement. This is a combined recapitulation of both primary and secondary themes which vertically (contrapuntally) merged! (Bar 188, see Example 7).20

Example 7. First Movement. 'Combined' Recapitulation.

Arrows show the starting notes of both themes,

which are the top and the bottom notes of the 'LDT'.

This ‘combined’ section most impressively reveals Shostakovich’s mastery of counterpoint. Strikingly, the composer leaves the two distant keys (B minor and Eb Major) of both themes intact. From one aspect, they sound together perfectly in distant registers supported by the Eb Major (the tonic of the secondary theme) and Bb Major (the parallel key of the primary theme) triads in the middle layer of texture. Because of the major triads in the two top layers, the entire episode is perceived as being in a major tonality, and Eb is perceived rather as a D# (an enharmonic equivalent).21 From another aspect, the major conflict between the two themes is neither entirely extinguished nor exhausted at this point. On the contrary, this section (the obvious major climax of the first movement) generates the continuation of dramatic development: as with many of Beethoven’s sonata forms, there is a second development, which occupies another 48 bars. In fact, this is the third development in this sonata form: the first is found inside the exposition (50 bars of the primary thematic section), the second is the actual development section and the part of the recapitulation section (90 bars), and the third comes after the recapitulation (‘terminal’ development, 48 bars). Thus, the development sections together occupy 188 out of the 284 bars of the entire first movement!

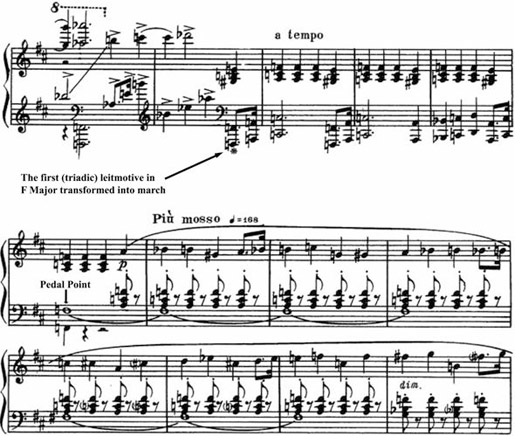

The closing theme of the recapitulation is preceded by the bridge – the new structural element whose function is very important (bars 197–201). (See Example 8, a tempo). Firstly, it introduces the new key, F Major; secondly, it produces a new image from the first triadic leitmotive – transformed here into the aggressive march (an obvious precursor of the ‘aggressive’ C Major episode in the third movement). The following closing theme (the ‘victim’ image) can therefore be perceived as a reaction to this aggression. The closing theme is presented on the groundwork of an F major pedal predetermined by the bridge (see Example 8, piu mosso). Using F Major for the first time in the Sonata, Shostakovich launches a bridge to the third movement in which F Major is one of the briefly touched-on keys (this corresponds to a tritone relationship, the most distant to the tonic) in the development (the middle part) of the variation theme. In the closing theme, F Major eventually appears to be the dominant to Bb Major, which is used for the return of the secondary theme. The latter serves as a bridge to the second development (bars 228–275).

Example 8. First Movement. Recapitulation.

a) Bridge to the Closing Theme (a tempo).

The first transformation of the triadic element into the aggressive march (the 'evil' image)

b) Closing theme (Piu mosso).

A pedal point on F - F# and ostinato of the F Major chords

The ‘second development’ section is a repeat of the first section of the actual development, but in the home key and in the composer’s ‘beloved’ marginal registers that create, together with soft dynamics and ‘complementary’ (additive) rhythm, a clear eerie effect (see Example 9). In bar 6 of Example 9 (see arrows), the bottom note is Dc (contra octave), and the top note is Bb4 – the distance between the top and bottom notes reaches almost seven octaves! Analogously to the actual development, the B minor emerges from the Bb Major through the instant melodic modulation (the same ‘common third’ tonal relationships), and the mode is also Phrygian (C natural is shown as accidental).

Example 9. First Movement, Second Development.

Eerie effect: soft dynamics, 'marginal' registers, 'complementary' (additive)

rhythm [Arrows show the longest distances (almost seven octaves!) in the Sonata

between the top and bottom notes]

In bar 248, the semiquaver note gesture returns and gradually flows into the coda. Because of the relentless motion, the point at which the coda ‘takes over’ is ambiguous; in my interpretation, it occurs in bar 257 where the opening phrase of the Sonata returns, creating an arch to the beginning of the movement with an unexpected crescendo and mighty chords at the end of the movement. The final two chords evoke the ‘horizontal’ contrast of B Major and B minor triads which will later be transformed into the ‘vertical’ contrast (in the climax of the third movement – B minor triad with a ‘split’ third).

As a ‘mid-summary’ of the above observation, listed below are the innovations of sonata form in the first movement of the Sonata and the unique characteristics of Shostakovich’s individual style, which clearly ‘identify themselves’ in this piece. (The analogies to Beethoven’s sonatas and the influences of other genres that appear in Shostakovich’s other works are also included in this summary.)

1. Modification of sonata form:

-

The exposition consists of two contrasting episodes (sections): the primary thematic section (non-divisible) and the secondary thematic section (inclusive of a closing theme).

-

The development and the following recapitulation of the primary theme are merged in one non-divisible episode creating the absorbed recapitulation in the primary thematic section of the recapitulation.

-

In the secondary thematic section of the recapitulation, the primary and secondary themes are merged contrapuntally to create the combined recapitulation of the two main themes.

-

Shostakovich applies the ‘Beethovenian’ sonata form pattern: a dramatic development exposes the conflict between ‘self’ (primary theme) and ‘fate’ (secondary theme). Through this treatment, the development sections of the first movement take precedence over the non-development sections, totalling approximately two-thirds of the movement’s duration; there is also a second, or terminal, development, as in many of Beethoven’s sonatas of the middle period. In fact, the development as a formal function permeates all the sections of the sonata form.

2. Other stylistic elements:

-

Scales and Modes:

-

The most unique stylistic element: the diminished tetrachords (the four-note modal structures within a diminished fourth). The top notes of these tetrachords are usually fourth or eighth lowered scale degrees.

-

The use of church modes: Lydian major (secondary theme) and Phrygian minor (beginning of both first and second development sections); showing the ‘major-minor’ contrast at the end of the movement (as the last reminder of the major conflict within the sonata form).

-

-

Key relationships: use of distant, chromatic mediant tonal relationships (B minor and Eb Major); use of ‘melodic’ (instant) modulations into the ‘common third’ keys: Eb Major – E minor (first development), Bb Major – B minor (second development).

-

Texture (another unique characteristic – an obvious influence of the composer’s orchestral works): the bottom and the top layers of texture are placed in the ‘marginal’ registers of the keyboard (the distance between the two ‘marginal’ layers often reaches five, sometimes seven octaves!), in some cases, with a middle layer between them, as in the ‘combined’ recapitulation of the two main themes. This kind of texture (hereinafter referred to as the rarefied texture) largely enhances the effectiveness of counterpoint.

-

Counterpoint: The composer frequently uses the contrapuntal technique in thematic development: imitations (notably, in the recapitulation of the primary theme), stratification of contrasting themes (notably, in the ‘combined’ recapitulation of the secondary theme); polyphonic methods of thematic (motivic) development (‘phased-in’ development, the gradual incessant unfolding of themes, open structures).

Conclusions

In the first movement of the Sonata, Shostakovich demonstrates his mastery of counterpoint and, in general, his adherence to the contrapuntal technique in thematic development. The composer, especially in his works of the middle period, shows a particular interest in polyphonic genres. For instance, the second movement of the Piano Quintet (1940) is a fugue; the fourth movement of the Eighth Symphony is a passacaglia (see Example 26). The rarefied texture greatly enhances the effectiveness and impressiveness of the contrapuntal work. It can be generalised at this point that in Shostakovich’s works, polyphony (horizontal aspect) takes precedence over harmony (vertical aspect).

» Next: The Second Movement (Largo)

« Previous: Piano Sonata No. 2—an Important Landmark in the Evolution of Shostakovich’s Individual Style

Footnotes

17 ‘The fact that Shostakovich was more vulnerable and receptive than other people was no doubt an important feature of his genius’ (E. Wilson, Shostakovich: A Life Remembered p. 183 (Princeton University Press, 1994).

18 In this article, the definition ‘self’ is used rather than ‘hero’, which is more suitable for Beethoven’s works.

19 At this point, it can be generalised that Shostakovich typically applies church modes rather than regular major or minor scales.

20 The composer’s tendency of merging a thematic material both horizontally and vertically obviously speaks for the ‘modern’ musical language based on polyphonic methods of thematic development.

21 As may be seen from subsequent development, this ‘bi-tonal’ episode launches the arch to the B Major episode in Variation 9 of the third movement (the cathartic episode).