Shostakovich's Piano Sonata No. 2 (cont'd)

The Third Movement (Theme and Variations)

a) Historical View: Polyphony of the Baroque era, Shostakovich and Bach

In the finale of the Sonata, Shostakovich illustrates once again his admiration for, and mastery of, the art of polyphony. The composer is very consistent in choosing the themes of polyphonic nature and, consequently, polyphonic methods of thematic development. The main theme (which becomes a theme of the following variation cycle) is a 30-bar unfolding of the two leitmotives: again, as in the first movement, the first motive is a triadic inverted structure (tonic 6/4); the second motive is a downward diminished tetrachord. This theme seems to be rooted in the monophonic structures of a Baroque piece – an unaccompanied melody, of a three-part symmetrical structure (9 + 12 + 9), with a middle part as a development modulating to distant keys and a recapitulation in the home key. Before examining the variation theme in more detail, it would be interesting to scrutinise the roots from which Shostakovich’s contrapuntal mastery grew.

Undoubtedly, Shostakovich, a great admirer of Bach’s music, was greatly influenced by the celebrated composer of the Baroque era. Among Shostakovich’s works that were obviously suggested by Bach is the piano cycle 24 Preludes written in the early period (1933). Shostakovich wrote these piano miniatures in 12 major and 12 minor keys (to my knowledge, a one-of-a-kind prelude cycle) – the idea obviously suggested by Bach’s Well Tempered Clavier (two volumes of 24 Preludes and Fugues each). The same idea was later implemented in Shostakovich’s ‘large-scale’ cyclic work 24 Preludes and Fugues (op. 87), written in 24 major and minor keys (albeit in a different order). As will be further shown, there are some strikingly similar stylistic components in the fugue themes of both Bach and Shostakovich. These elements include:

-

Large intervals (4th+) (Shostakovich’s favourites); in minor keys - extremely expressive diminished fourth, fifth and seventh, which are used as the bricks (motives) for the building of polyphonic themes;

-

A typical method of constructing polyphonic themes: filling in the large interval spans with the opposite—most often a stepwise—motion.

The theme of the Fugue No. 21 (Example 14) is a brilliant example of Shostakovich’s ingenuity in manipulating large intervals (mostly his favourites – fourths and sevenths). The composer alternates the direction of fourths and sevenths with the exception of two fourths going in the same direction (down); but, amazingly, there is no feeling of clumsiness here, but rather an effect of graciousness and playfulness because, in Shostakovich’s interpretation, two fourths are perceived as one seventh (the total of two fourths). The composer also camouflages any potential awkwardness with a gracious rhythm (repeated notes falling on upbeats).

Example 14. Shostakovich. 24 Preludes and Fugues. Fugue No. 21 in Bb Major.

Examples 15 and 16 illustrate the similarity of the intervallic structure between two themes - from Bach’s Well Tempered Clavier, Volume I and Shostakovich’s 24 Preludes and Fugues, op. 87. It is important to note that large intervals used by both composers (mostly sixths and sevenths) usually switch direction - up-down-up-down, etc. thus avoiding the ‘clumsy’ effect.

Example 15. J.S. Bach. WTC. Volume I. Fugue No. 3 in C# Major.

It is also of interest to compare the fugue theme (Example 16) and the clarinet theme from the finale of the Fourth Symphony (see Example 17). This is an example of Shostakovich’s ‘borrowing’ of thematic material from his own earlier works.

Example 16. Shostakovich. 24 Preludes and Fugues. Fugue No. 2 in A minor.

Example 17 (excerpt). Shostakovich. Fourth Symphony, Third Movement, Clarinet theme.

The theme of Bach’s Fugue No. 15 is an example of the commonly used method of constructing polyphonic themes (the filling in of the large intervals-leaps with the stepwise motion in the opposite direction). In our example, the sevenths are filled with a downward motion of seconds: from C to F# (the first seventh) and sixteenths (the second seventh). See Example 18. Of particular interest are comparisons of Bach’s and Shostakovich’s realisations of the same method in the themes of the same key (G Major) and of the same time signature (6/8). In Example 18 (Shostakovich’s Fugue No. 3), a ‘modern’ language stylistic upgrade is presented through an unresolved and accented F# in the first bar: this leading tone does not perform its leading functions. Yet the perception of the theme is as if it gradually resolves (‘deferment’ resolution) moving down to B – the first stable degree on a downbeat (bar 3 of Example 19). The initial ‘take off’ of the melody from G to F# (major seventh) is filled by the opposite motion of smaller leaps. The second half of the melody – vice versa: the major seventh leap upwards is then filled by a stepwise motion downwards (a more common method).

Example 18. J.S. Bach, WTC, Volume I. Fugue No. 15 in G Major.

Example 19. Shostakovich, 24 Preludes and Fugues, Fugue No. 3 in G Major.

Examples 20 – 21 illustrate the fugue themes from Bach that employ intensively diminished intervals; the extreme tension and instability found within these themes create a great potential for further development. Unquestionably, themes of this kind served as a rich resource for Shostakovich in creating his own polyphonic themes. For instance, the theme of a Fugue No. 4 (Example 20) is almost identical to Shostakovich’s monogram within the diminished fourth. The theme of a Fugue No. 16 (Example 21) shows the ‘hidden’ but still very expressive diminished seventh (Eb - F#), which is subsequently filled with the upward motion within the diminished fifth, also ‘hidden’ (F# - C).

Example 20. J.S. Bach, WTC, Volume 1, Fugue No. 4 in C# minor.

Example 21. Bach, WTC, Volume I, Fugue No. 16 in G minor.

The theme of the Fugue No. 24 (the last in the Volume I of WTC) is an example of gradually increasing tension and instability: it begins with a broken tonic triad and is then transformed into a series of resolutions (suspensions) which are never fully resolved until the final note in the new key (F#). The intervallic structure – use of augmented fourth (tritone) and two diminished sevenths – adds to extreme tension of this theme. See Example 22. Attention also should be drawn to the ‘broken’ melodic line (‘up-down-up-down’ pattern). This theme of ‘late’ Bach is a direct predecessor to Shostakovich’s themes of a similar kind. Shostakovich ‘updated’ Bach’s language (albeit very ‘modern’ for the 18th century) with additional diminished intervals, in particular his favourites – the diminished fourth and the diminished octave - creating an additional source of instability and tension. The variation theme in the finale of the Sonata is a brilliant example of how Shostakovich‘s themes are of the same kind as those rooted in Baroque (Bach’s) polyphony.

Example 22. J.S. Bach, WTC, Volume I, Fugue No. 24 in B minor.

Bracketed are the transpositions of a sequences.

For comparison, Shostakovich’s theme in Fugue No. 19 (see Example 23) is a worthy example. If in the previous example Bach made the most of diminished sevenths using a sequential development, here Shostakovich uses his favourite diminished fourth to considerable effect – not sequentially as would be expected, but by repeating it three times in ascension and in descent (only the last occurrence is a tone higher), thus creating a ‘pivotal’ type of melody. Two other elements that undoubtedly speak for the style of a modern composer are a) the use of a lowered second degree - Fb in Eb Major (very typical of Shostakovich, the ‘composer of flats’) and b) the 5/4 time (mixed meter).

Example 23. Shostakovich. 24 Preludes and Fugues, Fugue No. 19 in Eb Major.

Brackets show the return of the Eb (tonic): the 'pivotal' type of the melody.

A number of Shostakovich’s themes can be found with the same intervallic content. This is an absolute patent of Shostakovich in his exploitation of wide intervals – both diatonic (as in the main motive of the second movement) and chromatic, usually with ‘flatted’(lowered) tones (see the variation theme - Example 24).

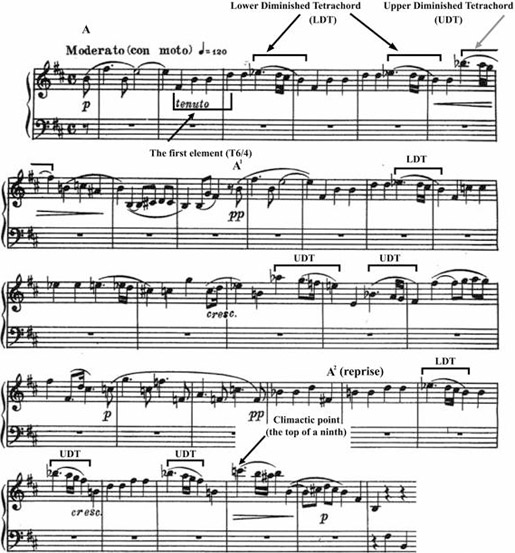

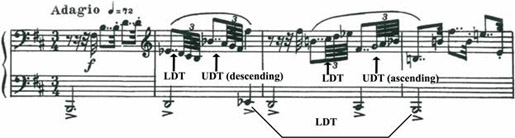

b) The variation theme: diminished tetrachords

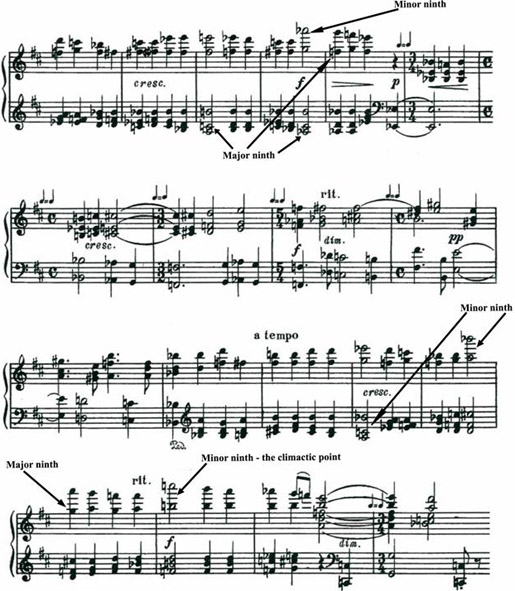

The variation theme is built primarily on two of the Sonata’s principal leitmotives. The first is a melodically exposed tonic six-four (T6/4) chord (analogously, the opening motive of the first movement is the melodically exposed tonic six-three chord (T6/3) – see Example 2 on page 6).23 The following motive (Eb – D – C# - B) is clearly the ‘LDT’. (See earlier in this article a description of the two diminished tetrachords.) Further unravelling of the variation theme ‘delivers’ the alternative version of the diminished tetrachord – the ‘UDT’, which appears to be the actual (untransposed and unmodified) second leitmotive of the Sonata (Bb – A – G – F#). See Example 24. The intervallic structure of the variation theme, which is predominantly based on diminished fourths and eighths (with the upper notes forming the ‘summit’ of the tetrachords), along with a minor ninth (with the upper note becoming the climactic point of the theme), later became the quintessence of the composer’s melodic style.24

Example 24. Third Movement. The Variation Theme.

It is striking how deliberately Shostakovich ‘prepares the ground’ for the appearance of both motives in the third movement – not only by exposing them in a ‘hidden’ form at the very beginning of the Sonata, but also through the tonal centres of the two main themes of the first movement (B minor - Eb Major – the upper and lower notes of the ‘LDT’. (This also creates the tonal ‘hyperlinks’ between the two movements.)

The variation theme exposes the ‘UDT’ in two versions: the original version (from Bb downward) and the transposed version (from Ab downward). If further transposed to start from Eb (parallel to the ‘LDT’ with the difference of C – C#), the ‘UDT’ becomes Shostakovich’s ‘monogram’ which will later permeate many of his most prominent works.25 It can be assumed at this point that such premeditated preparation of the ‘diminished tetrachords’ in the Sonata stems from Shostakovich’s clear understanding of the importance of these motives, not only to the unity of the sonata cycle, but also to the full expression of the composer’s ‘self’ through the deliberate crystallisation of the ‘monogram’ motives.

The structure of the variation theme deserves special attention. The 30-bar theme is a three-part structure. The first part functions as the exposition of the main motives of the theme (bars 1-9). The second part functions as a development (bars 10-22) – a sequential development of the main motive which transforms the ‘LDT’ into the ‘UDT’, with modulations to distant keys (F Major is clearly present – the tritone relationship to B minor). The third part is a modified recapitulation reaching the climactic point in bar 28 (the top note of a ninth). It is extremely important to remember that the climax of the variation theme occurs in bar 28 in a 30-bar theme. As will be later shown, the structure of the theme predetermines the structure of the entire variation cycle.

The scale, with all the notes used in this theme, actually includes thirteen degrees (the seventh degree is shown twice with its enharmonic equivalent, which is the lowered eighth degree of the scale). This chromatic scale is a typical Shostakovich’s scale inclusive of lowered fourth, seventh and eighth degrees. See Examples 25 and 26.

Example 25. The Scale Used in the Variation Theme.

Lines show the enharmonic equivalents—Bb - A#; arrows show Shostakovich's typical lowered scale degrees—IVb, VIIb and VIIIb—that usually serve as the summits of the diminished tetrachords.

Example 26. Eighth Symphony, Fourth Movement, Passacaglia Theme.

Bracketed is the upward 'UDT'. As in the scale shown in Example 25, the seventh degree is presented in two enharmonic equivalents: Fx (the bottom note of the theme, the 'leading' tone with the upward tendency) and G natural (the top note of the theme, the lowered chromatic tone with the clear downward tendency).

c) The Variation Cycle

The composer chooses the form of variations for this finale (rarely found in the finales of sonata cycles; well-known examples include the finale of Beethoven’s Third Symphony [Eroica] and the finale of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony). In this movement, the composer reveals his mastery in creating rhythmic, textural and genre transformations of the main theme. The whole variation cycle of this finale can be presented on a ‘hyper-function’ level: the ‘hyper-functions’ can, in certain ways, be paralleled to the formal functions of the sonata form (the lower level) and to the movements of the sonata/symphony cycle (the higher level).

On a ‘hyper-function’ level, the first two variations function as the exposition of the variation theme. In Variation 1 (bars 31–60), the composer simply ‘dresses’ the theme with an accompaniment. The theme itself is intact, except for one note (E natural instead of Eb in the recapitulation). In Variation 2 (bars 61–90), rhythmic and textural changes occur – the rhythm becomes quaver triplets, which comfortably ‘wrap-up’ the theme from both sides – from the top and the bottom – exchanging textural positions; yet the theme remains intact. (This variation calls to mind the first movement’s exposition with its rhythmic and textural patterns.)

Variation 3 (bars 91–128) is the first point at which the composer begins to exploit the theme itself. It might be argued that the development of the variation cycle begins here (Piu mosso). Motivic development of the theme is mainly based on rhythmic changes. With an articulation marking of staccato, this variation functions as the first scherzo of the sonata cycle.

Variation 4 (bars 129–162) reverts to Tempo I. See Example 27. In this variation, the composer uses a chordal texture voiced by the theme in the soprano register. Of particular interest here is an assessment of ‘verticalities’ in this variation.26 The texture carefully follows the melodic contour: since the melody fluctuates, gradually extending the range and reaching the uppermost note, the texture ‘pulsates’ and ‘breathes’ accordingly, alternating areas of lower and higher density. The higher notes are harmonised with denser chords, larger intervallic structure and wider ranges. The culminating notes acquire the densest vertical realisation.

As shown in Example 27, Shostakovich’s favoured wide intervals (seventh and ninth) largely permeate the vertical sonorities. For instance, the Ab3 in bar 19 of Variation 4 is the top note of a ninth; the lower portion of this chord includes both the seventh and the ninth. The Bb3 in bar 30 is the top note of the ninth A2 – Bb3, and the highest note C4 is the top note of the ninth B3 - C4. Thus, Variation 4 is a perfect example of modern tonality – tonal functions are ‘absorbed’ and ‘dissolved’ by textural and melodic (polyphonic) functions. Variation 4 is also the first where meter and tempo frequently change (an obvious association with tempo rubato and changing meter in the first part of the second movement). The ‘hyper-function’ of this variation is that of a slow movement within a sonata cycle.

Example 27. Third Movement. Variation 4.

The ninth permeates vertical sonorities.

Variation 5 (bars 163–235) is another scherzo and a major turning point within the entire variation cycle – most noticeably, the key changes here for the first time in this movement. It can be argued therefore that Variation 5 establishes the middle section of the variation cycle. Thus, on a ‘hyper-function’ level, Shostakovich actually creates a three-part structure, easily recognised by the key plan. The key signatures of B minor are annulled, and the composer applies accidentals to offer an idea of the possible key. The first episode of Variation 5, featuring the main motive, delineates F minor (tritone relationship to the home key). Most importantly, Shostakovich applies here a character (genre) transformation of the main theme for the first time in this variation cycle. In bar 38 of this variation (recapitulation of the theme), the new image suddenly appears in the ‘bright’ key of C Major (See Example 28, the upbeat of bar 3).

Example 28. Third Movement. Variation 5, C Major ('Martial') Episode.

C Major had been suggested from the opening of this variation through the estrangement of preceding key signatures, but in actual fact, it appears in bar 38 as a recognisable and ‘active’ key. In the C Major episode, the main motive is transformed to another genre – the song-like melody becomes a march ‘transferred’ from minor to major. But even more importantly, the march theme is split into the two conflicting motives: the C Major upward motive – tonic six-four (the ‘evil’ attack) and the downward ‘LDT’ which is transposed a whole tone up (F – E – D# - C#), then a fifth up (C – B – A# - G#); then, it is followed by the ‘UDT’ (F – E – D – C#). (See Example 28, the second and the third systems, the left hand part.) It is unusual that a theme in 3/4 time be perceived as a march. The martial effect is created through a) strong dynamics (f); b) ‘trampling’ rhythm (typical of Shostakovich) and c) ‘orchestration’ of the theme (a fanfare-like triadic motive and a dense - doubled in sixths - melody) that, altogether, evoke similarities to those symphonies by Shostakovich that feature brass - trumpet and trombone - solos.27 See Example 29.

Example 29. Fifth Symphony, Second Movement, the Secondary Theme.

Martial effect: an octave upbeat, strong dynamics, heavy 'pin' accents, brass timbre (the SOLI are the trumpet and trombone parts); Arrows show the sevenths, which make the 'pure' C Major sound dissonant and 'distorted'

It is important to note that the C Major episode is the first episode in the variation cycle that exposes the major conflict of the Sonata (between ‘self’ and ‘evil’) within the same variation and within the same theme even. A close look at the use of keys in the Sonata leads to another important conclusion: there are common threads between episodes in the same key. In this particular example, the key of C Major used in Variation 5 brings a clear association with the middle section of the second movement (the ‘mesmerising’ episode, also in the key of C Major). Semantically, the ‘soft’ version of the ‘evil’ episode in the second movement is transformed into the aggressive ‘martial’ version in Variation 5 of the third movement.

Variation 6 (bars 236–291) is an example of a rhythmic variation that is entirely built on dotted rhythms (shown with dots or with the appropriate rests). Semantically, this variation illustrates yet another ‘evil’ attack (the second in the variation cycle). On a ‘hyper-function’ level, Variation 6 functions as another scherzo of the sonata cycle. The difference between the first and the second scherzos (Variations 5 and 6) is that the first scherzo (at least in the beginning) peacefully ‘plays’ with the ‘self’ motive, whereas the second ‘plays’ with the triadic motive which is readily transformed into the ‘evil’ image (analogous to the C Major episode of the previous variation). The establishment of a dotted rhythmic pattern in this variation creates a seamless background for the rest of the variation cycle (except for the coda and only one bar in Variation 9 – see further discussion). From one variation to the next, this relentless rhythm becomes more and more disturbing, thus creating the poignant trembling effect.

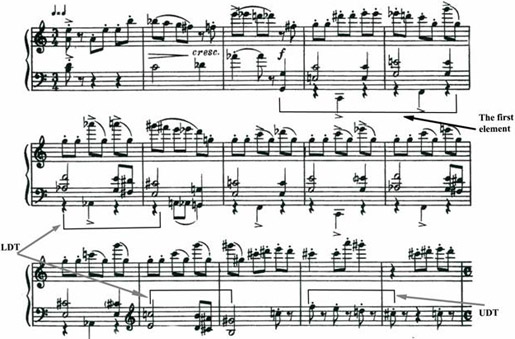

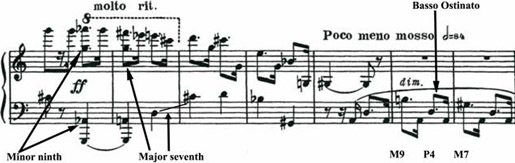

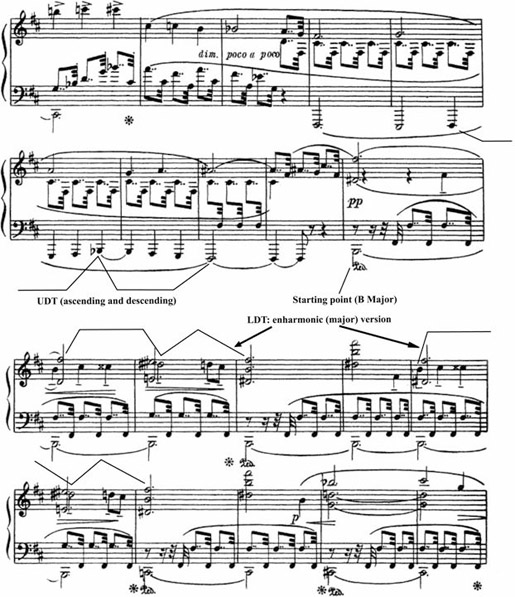

In Variation 7 (bars 292–378), the dotted rhythm is transformed into the basso ostinato, once again permeated with the composer’s favoured intervals - fourths, sevenths and ninths (see Example 30).28 This episode (Poco meno mosso) brings two new elements – E Major triads alternated with the Bb six-four chord. Through a combination of the ‘trembling’ ostinato, the key of E Major and the rarefied texture, Shostakovich creates a pre-cathartic effect (the actual cathartic episode will appear in the next variation). This episode is the first attempt to bring calm after the ‘evil’ attacks, but the continuous ‘trembling effect’ retains a very nervous feel to the music.

The treatment of Variation 8 (bars 379–407), similar to the original theme, is most obviously rooted in the Baroque era. This episode can be most easily imagined as part of a Baroque passacaglia – the theme in the low bass (based on the ‘LDT’) constitutes groundwork in respect of the ‘baroque’ theme – the hemidemisemiquaver transformations of both ‘LDT’ and ‘UDT’. In bar 2 of Example 31, the two tetrachords are shown in downward motion; in bar 3 – in an opposite, upward motion. A slow tempo (Adagio) and double-dotted rhythm add to the tragic allure of the variation. The B minor key returns, signalling the tonal recapitulation of the variation cycle. The return of the B minor key suggests that this variation, on the level of hyper-functions, is not only tonal, but that it is also the modified (intensified) thematic recapitulation, whilst being at the same time a tragic climactic point of the entire cycle. (The main motive articulated with ‘pin’ accents recurs clearly in low bass, and then transfers to the middle voice.) It is important to note that the entire ‘baroque’ episode is dynamically very strong (f – ff), which additionally supports its climactic role in the variation cycle (the ‘strong’ climax). The ‘baroque’ episode gradually flows into the ‘soft’ climax of the cycle – Variation 9. This episode (in warm and relaxing B Major – a parallel to the home key) is the logical and emotional continuation of the E Major episode of Variation 7 consisting of similar elements (the ‘trembling’ ostinato on the dominant of B minor [F#] in bass, the B Major chords in the high register).

Example 30. Third Movement. Variation 7.

Pre-Cathartic or trembling episode (Poco meno mosso). Arrows show the composer's favorite ninths, sevenths and fourths that permeate both horizontal and vertical lines.

The B Major episode of Variation 9 (bars 408–444) is one of the most remarkable episodes in the Sonata and, arguably, Shostakovich’s entire musical output. The astonishing expressiveness of this episode is due to the so-called cathartic effect, which is, to my mind, a musical phenomenon quite unique to Shostakovich.29 Only an artist who had been subject to the levels of stress and intimidation in his life and career could have hoped to create such an effect. Typically, the cathartic effect occurs after highly dramatic, even tragic moments in Shostakovich’s music, bringing feelings of peace and relaxation that are very much in an almost desperate need. In fact, the extreme dramatic tension in many of Shostakovich’s works, a tension that would certainly have created a depressed, even hysterical impression, now appears soul-cleansing and brings tears of joy to the eyes; and this is indeed what the composer needed in order to survive. In my view, the cathartic episodes in many of Shostakovich’s tragic works constitute a very important feature of the ‘Aesopian’ language, being understood correctly only by those who were the victims, not the oppressors.

Example 31. Third Movement, Variation 8.

Beginning of the 'Baroque' Episode—the tragic climax of the variation cycle

The episode actually starts from F#, which first sounds like a tonic of F# Major (See Example 32, bar 4), but then turns into a dominant of the upcoming B Major. F# in the low bass (contra octave – Shostakovich’s typical ‘marginal’ register that creates the eerie effect) is the first note of the ‘UDT’, which itself creates a grounding for this episode, leading back to its opening – the B Major triad (bar 10 of Example 32).

The most expressive element of this episode and one that conveys the sense of catharsis to its climax is the main motive in the middle voice transferred from B minor to B Major (notated as B – C# - Cx – D#). The dissonant chord (a harmonisation of D#) creates an extreme, tortuous tension, only slightly softened by the dynamics (pp), before being gradually resolved into the tonic of B Major. The B Major episode is an excellent example of Shostakovich’s interpretation of tonality and a tonal centre. The long-awaited tonic of B Major brings great relief, emerging out of dramatic development exposed in previous episodes of all the Sonata’s movements. In true style, Shostakovich finds a ‘simple’ means of creating the climax of this episode: firstly, the minor and the major triads, contrasting horizontally this far, here merge in a single vertical sonority (the tonic triad with a ‘split’ third – see Example 32). Secondly, on the foundation of the ‘merged’ triad, the ‘simple’ diatonic motive, strikingly expressive in its simplicity, reaches a climactic G3 by rising a minor sixth and then descending a minor second to F#. Thirdly and most strikingly - the relentless ‘trembling’ ostinato is suddenly halted – simply for this single bar and a half, thus creating a veritable climax of the cathartic effect. In my interpretation, this, the climactic point of the entire movement, represents an exhausted, yet at the same time, fully relaxed ‘self’. (In my analogy, this moment is similar to that at which one finally reaches orgasm, followed by exhaustion and then gradual relaxation. Your body feels weightless; your soul is freed from suffering and earthly burdens.)

There is one more captivating fact to add to this picture. If we recall where the climactic point of the variation theme occurred - this was in bar 28 of a 30-bar theme; if we note where the overall climax occurred – this happens in bar 431 of a 475-bar third movement. A simple mathematical calculation to compare the equivalent percentages (equivalent to 28/30 and 431/475) shows that they are almost identical (93% and 91%, respectively). Indeed, the structure of the variation theme (with its ‘long-reaching’ climactic point) appears to have predetermined the structure of the entire variation cycle!

Example 32. Third Movement, Variation 9.

The Cathartic Episode. Starts with the low B establishing the B Major.

Example 32 (cont'd).

The Climax of the Cathartic Episode (also the climax

of the third movement and the entire sonata cycle)

Reality inevitably returns. Variation 10 reinstates the feeling of the endless rush of life, the disquiet one feels in having to fight for a better existence. In this variation, the main theme returns, but in reduced form: the composer skips its exposition, starting at the development. See Example 33. The finale’s coda is entirely based on the main motive, which ‘roars’ twice in the low register, before the ‘LDT’ is repeated twice more until the constant gesture semiquaver finally stops at the low F#. It clearly functions here as a dominant, which becomes the foundation for the last repetition of the ‘LDT’. The concluding bars of the finale are the composer’s final attempt to bring back the major chords, but this is short lasting. The piece ends with the tonic chords on pianissimo in the lowest register of the piano. Life has made its full turn and ended with little hope ‘for the light at the end of the tunnel’.

Example 33. Third Movement, Variation 10 (Coda).

Semiquaver motion returns

Conclusion

Shostakovich could never fully hide his genuine feelings and thoughts in his music. His sensitive ear and troubled soul so often reveal themselves. In the coda of this ingenious finale, with its ceaseless semiquaver motion, the composer creates a clear arch to the beginning of the Sonata, signifying that the final variation functions as a coda for the entire three-movement sonata cycle. More broadly, the coda reminds us, in many ways, of the tragic finale (following the Funeral March) of Chopin’s Sonata No. 2 in Bb minor. Both finales can be associated with the autumn wind that blows away the dead leaves just as humanity sweeps away old traces of memory.

Whoever might criticise Shostakovich for his political views and his attempts to compromise with the regime, should listen to this music. It speaks for itself and for a great composer who was able to survive during the most horrific period in Russian history, who was able to relate to all those who care to listen not through the words he was being forced to write or to say, but by means of his musical language. Like Beethoven more than a hundred years before, Shostakovich bore his mission as a creator of immortal music, while fighting the brutality and the cruelty of the world in which he lived.

» Next: Summary

« Previous: The Second Movement (Largo)

Footnotes

23 At this point, it is safe to generalise that in Shostakovich’s works of the middle period, it becomes a common rule to present the tonic elements (in most cases – very briefly) at the beginning and at the end of the composition (or at some cadential points). The tonic serves as the initial ‘launch pad’ of the piece, after which the tonal deviation (modulation) process begins gradually reaching distant keys and finally reverting to tonic. For instance, the development process of the variation theme reaches as far as F Major (a tritone relationship with the home key), then returns to the tonic at the cadential point.

24 The variation theme is also a perfect example of polyphonic themes based on the principle of filling in the wide leaps with the opposite stepwise motion. The variation theme of the Sonata is an obvious predecessor to the Passacaglia theme in the fourth movement of Shostakovich’s Eighth Symphony composed only a few months later. This becomes obvious when examining the mode structure of the Passacaglia theme (in the key of G# minor) - use of the lowered fourth (C natural) and the lowered eighth (G natural) degrees and the upward ‘UDT’. See Example 25.

25 Interestingly, I. Strachan, the author of an article Shostakovich’s “DSCH” Signature in the String Quartets (DSCH Journal No. 10, 1998), lists the variation theme of the third movement of the Sonata among Shostakovich’s works where the ‘anagram’ DSCH is used in a ‘scrambled’ order. In light of the ‘tetrachordal’ structure of the variation theme, it seems to be more precise to state that in the Sonata, the ‘UDT’ in its transposed form (fifth up) is an obvious precursor of Shostakovich’s ‘monogram’.

26 The word ‘verticalities’ is intentionally used in this article instead of ‘harmonies’: Shostakovich’s harmony (vertical structures) is obviously subordinate to polyphony (horizontal melodic tendencies) and texture (density of vertical structures).

27 The best example is the Fifth Symphony, second movement, where a theme on trumpet and trombone recalls the C Major episode of the Sonata (C Major, 3/4 time, ‘upbeat from the dominant’ structure, and a ‘dense’ melody doubled in thirds) - see Example 29.

28 At this point, it can be generalised that these three intervals are omnipresent in the Sonata.

29 The Webster Dictionary gives the following definition of the catharsis (from Greek katharsis): A purifying or figurative cleansing of the emotions, especially pity and fear, described by Aristotle as an effect of tragic drama on its audience; a release of emotional tension, as after an overwhelming experience, that restores or refreshes the spirit.